The posts discuss 8 themes:-

- How to write a Grant Application

- Strategy for writing grant applications

- Writing Style for Grant Applications

- Giving and Receiving Feedback on Grant Applications

- Dealing with referees reports and with rejection

- Interviews and Talks

- Software

- Academic Life and Afterlife

How to Write a Grant Application

- This post describes the on-line workshops that I developed in 2020 and explains why the interactive on-line workshop is better than the face-to-face workshops I used to deliver between 2013 and 2020.

- The posts described below explain the approach to grant-writing that I teach in the on-line workshops:-

- This post explains why it is unwise to write your case for support so that only an expert can understand it.

- This post explains why the readership problem is the most important problem to consider when you are writing your case for support.

- The magic formula for a case for support that solves the readership problem.

- This post explains how the distinctive structure of the case for support ensures that committee members extract the information they need from it without reading it carefully.

- Before you start writing you need to design your research project.

- Start by getting the structure of your case for support as a set of key sentences.

- A recipe for the key sentences

- How the key sentences work.

- Key sentences work so well for the reader so you should use them to structure your case for support even if they don’t help you to write it.

- Make sure that the aims match the objectives

- Why you need a good introduction and how to write it

- How the Background sells the project

- A good summary will help a committee understand your application

- An exercise to generate a good opening sentence

- This post explains that you should have fewer than four and more than two items in a list and that you should format lists so that items are on separate lines.

- Adapting the key sentence approach to other grant schemes: NIH K99/R00

- The key sentence approach takes 2 weeks or less to generate a case for support

- You need a project if you want to practise writing key sentences. If you don’t have a project you can practise by pretending you are applying for funding for your PhD project.

- You can practise writing key sentences to sell other things than a research project. Here is a set that I wrote to sell my grant-writing workshop.

- The quick way of starting a grant application is to write a set of key sentences. There is way that looks easier but it usually ends up being much more difficult.

Strategy for Grant Applications

- The importance proposition explains that the first question a funder asks about your grant application is whether it describes a project that meets their priorities.

- Training people to write grant applications doesn’t necessarily open the funding floodgates.

- Whatever your writing approach, always start by figuring out what the project is.

- Before you start writing you should check whether your proposed project is likely to be viable and fundable

- Record this essential information about your project so that you can check whether it is fundable and viable.

- If you start writing a grant application before you are ready you might never finish

- You shouldn’t write a grant application unless you need a grant. And if you need a grant, you should be prepared to write several applications

- This post explains why it’s better to write a good grant application, even though most successful applications are poorly written.

Writing Style for Grant Applications

- You will need to repeat yourself: make sure that you use exactly the same words

- Start each paragraph with the punchline

- Don’t fall into these traps.

- Try to avoid these common bad habits

Friendly fire: Giving and receiving feedback

- A five minute test to see if you have the right bits in the right places

- How to give your grant application a more searching test

- How to give useful feedback

- How to get a reluctant critic to tell you what you need to know

- How to reshape your case for support

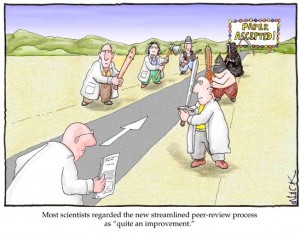

Dealing with referees reports and with rejection

- Why committees and referees might not agree with each other

- How to respond to referees

- Recycling a rejected application

- First steps for dealing with rejection

Interviews and talks

Software for Writing Grant Applications

Academic life & Afterlife

- I recommend you read “getting to yes” if you have to manage people or negotiate

- My approach to the problem of writing and reading employment references

- It is always best to act as if you assume that the people you are dealing with are being reasonable

- Academic Management is important

- Introductory post on this blog

- My feelings on finally becoming my own boss

- Reflections on the first couple of years of running the company.

- Comparing my grandson’s first computer with mine.

- If you do not reduce work when you commit time to other activities you will not improve your work-life balance: you will make it worse

- This post announces the death of Amanda Parker. Her obituary is here.