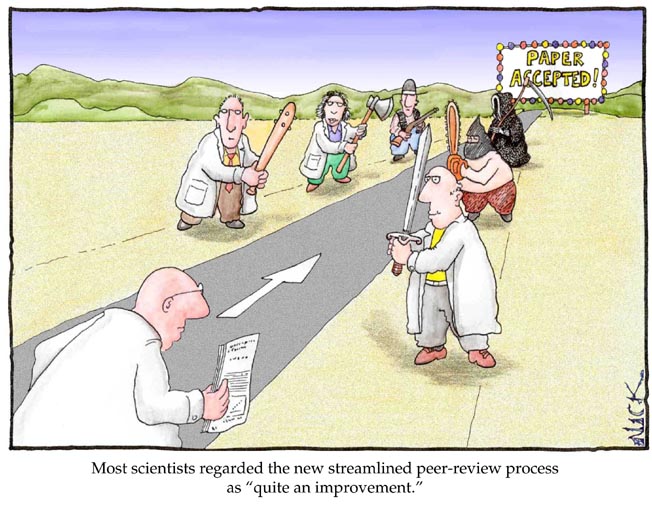

Is there a recipe for the 10 key sentences?

Recipe for Key Sentences in a Grant Application?

This post is about an easy way to work out what to write the 10 key sentences that define a grant application. There are two reasons I think it’s worth writing even though I have written about the key sentences several times recently.

- A good set of key sentences is half-way to a case for support. A really good case for support consists of nothing more than the 10 key sentences and the text that fills in the detail and convinces the reader that the key sentences are true. Of course this extra text is much more than filler, but it is a great help to have the key sentences because they define the task of the rest of the the text.

- I have been working with a couple of clients who, even though they are clever people and they get the idea of key sentences, find it really hard to write them. So I have been on the lookout for a good way of making it easy to write a good set of key sentences.

Skeleton sentences, which Pat Thomson’s excellent blog recommends as a way of handling difficult but often repeated writing tasks such as framing a thesis introduction, or introducing a theoretical framework, look perfect. You take a key sentence that works; you separate it into its component parts and identify the parts that are specific to its current use and the parts that are generic. Then you turn the generic parts into a skeleton and replace the parts that are specific to its current use with equivalent parts that are specific for your use, and you have your own equivalent sentence.

Complication warning

I should perhaps warn you at this stage that although this post really does simplify the process of writing key sentences, it is quite detailed and it doesn’t do anything else. So if you aren’t trying to write a grant application you should probably just bookmark the page and return when you start writing your next grant.

I should perhaps warn you at this stage that although this post really does simplify the process of writing key sentences, it is quite detailed and it doesn’t do anything else. So if you aren’t trying to write a grant application you should probably just bookmark the page and return when you start writing your next grant.

Finally, before I get down to the nitty gritty, I have two strong recommendations.

- It is very risky to start writing key sentences before you have worked out the details of your research project. As soon as you have done that you should divide it into three or four sub-projects, each of which will find something out, establish something, or develop something. This post tells you how to do that.

- Although it makes most sense to read about the key sentences in numerical order, it’s pretty hard to write them in that order. I’ll make some suggestions about writing order as I explain the recipes.

So, what would skeletons for the 10 key sentences in a grant application look like? I think I can tell you in 9 of the 10 cases. I will describe them in numerical order, which is the order in which the reader will encounter them.

Key sentence 1, the Summary sentence

The first sentence of the proposal, key sentence 1, is probably the most complex and variable of the key sentences. It gives a simple overall statement of what the project will achieve, ideally it will relate that achievement to a big important problem and will also include something distinctive about how the project will achieve it in a way that will make it clear that you are a suitable person to do the project.

A minor variation of a sentence I suggested in an earlier post about key sentences, does all this. It has four parts, which are numbered.

- This project will develop a new potential treatment for stroke

- by identifying, synthesising and testing suitable molecules

- from a family of novel synthetic metabolic inhibitors

- that we have discovered.

A skeleton representation of the four parts would be:

- This project will [your own description of how it will make partial progress towards solving a huge, important problem – in the example it’s “develop a potential solution”]

- by [ your own much more specific description of what it will actually do]

- [your own assertion that the project is novel or timely – e.g.”novel synthetic metabolic inhibitors”]

- [your own claim to “ownership” of the project – e.g.”that we have discovered”].

I would suggest that you leave the first key sentence until near the end. I would also suggest that you content yourself with a rough draft initially. You will have plenty of time to refine it as you flesh out the detail int he case for support.

Key sentence 2, the Importance sentence

The second key sentence states the importance of the specific outcomes promised by the project. The following sentence does this in two ways. The first clause gives some evidence that the big problem is really important. The second clause asserts that the specific problem that will be solved by the project is an important aspect of the big problem.

- Stroke is one of the commonest causes of death and disability in the working population;

- one of the most promising new avenues of treatment is to shut down brain function reversibly using a metabolic inhibitor, we have yet to identify a suitable molecule.”

Its skeleton is

- The [huge important problem] is [your own statement that demonstrates with evidence that the problem is very important for one or more of health, society, the economy and the advance of knowledge and understanding];

- [your own statement that the project outcome will contribute to solving the huge important problem].

I think that the second key sentence is definitely the last one to write.

Key Sentences 3-5, the Aims sentences

Sentences 3-5 would be the first and the easiest sentences for you to draft. They are what I used to call the “we need to know” sentences. There is one for each sub-project. An example from our hypothetical stroke project would be:- We need to identify which molecules in this family are most effective as reversible inactivators of brain tissue. The skeleton for an aims sentence would be something like this.

We need to [know or establish or develop]+[your own statement of whatever the sub-project is going to discover or establish or develop].

Each of the aims sentences introduces a section of the background to the project (the bit where you justify the need for your research) in which you convince the reader, by citing relevant evidence, that the key sentence is absolutely, starkly and compellingly true. You would also re-use the same sentence in the introduction to the case for support and in the summary.

Specific Aims

Some funders – notably NIH and the UK research councils, like you to talk about aims, or even specific aims. For this you create a compound of all 3 aims sentences of the following form.

We have three (specific) aims:-

1) to [discover, develop or establish] [your statement of whatever the first sub-project is going to discover, develop or establish]

2) to [discover, develop or establish] [your statement of whatever the second sub-project is going to discover, develop or establish]

3) to [discover, develop or establish] [your statement of whatever the third sub-project is going to discover, develop or establish]

Key Sentence 6, the Project Overview sentence

This sentence introduces the description of the research project by saying what kind of research it will involve, something about the facilities it will use – especially if these are distinctive in some way, and what it will discover. It may say something about the resources it will use. It is very similar to sentence 1 but it might have a bit more information about the kind of research and the specific outcome.

The following sentence, in italics, is an example related to our example of sentence 1. The proposed project will be a mixture of synthetic chemistry to produce candidate molecules and in vitro physiology to test their efficacy in producing reversible inactivation of brain slices in order to identify a potential treatment for stroke. The skeleton sentence, is The proposed project will [general description of research activity] to [specific description of research outcome] in order to [weak statement indicating partial progress towards solution of huge important problem].

I think that the project overview sentence should be written after the sub-project overview sentences.

Key Sentences 7-9: Sub-project Overview sentences

Each sub-project has a “this will tell us” sentence that matches the “we need to know” sentence but is a little bit more complex. It begins with a clause that summarises what you will do in the sub-project and continues with a main clause that says what it will tell us. For example:- We will use voltage sensitive dyes to assess the activity and responsiveness of brain slices in order to measure the effectiveness of different molecules as reversible inactivators of neural activity.

The skeleton would be:- We will [do the relevant research activity] in order to discover [the thing that we said we needed to know in the corresponding Aims sentence].

If your funder asks you to list research objectives as part of the grant application, or if it suits your writing style you can phrase (or rephrase) your “this will tell us” sentences as statements of objectives. They would read like this.

The research objectives are as follows:-

1) to [do the relevant research activity] in order to discover [the thing that we said we needed to know in the corresponding Aims sentence].

2) to [do the relevant research activity] in order to discover [the thing that we said we needed to know in the corresponding Aims sentence].

3) to [do the relevant research activity] in order to discover [the thing that we said we needed to know in the corresponding Aims sentence].

Key sentences 7-9 can be written as soon as you like. You should have everything you need to write them right at the start. However, they are a bit more tricky than key sentences 3-5, which is why I recommend that you start with those.

Key sentence 10, the Dissemination sentence.

The dissemination sentence should introduce a description of the projects dissemination phase. It may say something about what you will do with the results to create a platform for future research – by you or by others. The range of possible dissemination strategies is too great for me to construct a skeleton, however I will comment on the relative importance of dissemination versus building a platform for future research. The relative importance depends somewhat on key sentence 2.

Dissemination beyond the research community is important if key sentence 2 claims that the importance of your project is related to some practical problem or opportunity (curing a disease, making a technological breakthrough). Your dissemination plan will need to include steps you will take to make sure that the results are put to use and your project. You may also be requesting funds for dissemination activities.

On the other hand, if the importance of your project is purely to do with its potential to advance your subject, you probably do not need to say much about dissemination activities although it might be important to talk about communicating the results to your research community by publication and conference activity.

In the Research Funding Toolkit we explain that funding decisions depend on whether the case for support makes four propositions. It has to convince the reader that it is important, that it will be a success, that the team are compentent and that the grant will be value for money. We refer to the four propositions as importance, success, competence, and value for money. In the next few posts I want to deal with the four propositions in turn.

In the Research Funding Toolkit we explain that funding decisions depend on whether the case for support makes four propositions. It has to convince the reader that it is important, that it will be a success, that the team are compentent and that the grant will be value for money. We refer to the four propositions as importance, success, competence, and value for money. In the next few posts I want to deal with the four propositions in turn.