A couple of weeks ago I described deadly sins that grant-writers commit deliberately. This week I am dealing with sins that are just as deadly but much harder to avoid. The sins of omission just creep into your writing without you noticing and you have to make special efforts to remove them.

A couple of weeks ago I described deadly sins that grant-writers commit deliberately. This week I am dealing with sins that are just as deadly but much harder to avoid. The sins of omission just creep into your writing without you noticing and you have to make special efforts to remove them.

The sins I want to deal with are Complex Sentences, Long Paragraphs, Poor Flow and failing to match the background to the project. They all meet the definition of sin that I coined last week: “Anything that makes it hard for a committee member to pick up a clear understanding of the rationale of your research project, what it will discover and why that is important, is a sin. So is anything that makes it hard for a referee to get a clear picture of the detailed reasoning in your argument and the detailed description of your intended research activities. Referees and committee both work under time pressure, so anything that slows them down is also a sin.”

Complex sentences are really difficult to avoid. They appear spontaneously in your draft. Most people can’t avoid writing them whenever they are trying to write something difficult – like a grant application.

That’s OK. Writing complex sentences isn’t the end of the world. Not unless your first draft is the end of your writing process. You must expect your first draft to be full of sins and you need to cast them out. You need to hunt through your draft and convert all the long, complex sentences into short, clear simple sentences. As a rule of thumb, you should redraft any sentence longer than 30 words or containing more than 1 verb or beginning with a digression – a phrase that is introduced by a word like “although”. And if it’s the first sentence of a paragraph you also need to make sure that the main message of the sentence fits on the first line.

It’s OK for complex sentences to appear in your first draft because that is usually the easiest way for you to write it. But it’s not OK to leave them there. You have to replace them with simple sentences. This may involve breaking them up, or turning them round and it will take time, but you will get quicker with practice. Your final draft must be easy to read, and to speed read. Most of the people voting on your grant application will speed-read, or skim it. So if what you send them is full of complex sentences that have to be decoded carefully then they will not get your message, and you will have less chance of getting funded.

Long paragraphs are bad for two reasons.

- I pointed out in my last post that most of the people scoring your grant will speed-read your case for support. Speed-readers read the first line of every paragraph provided there is white space between them. The longer your paragraphs, the less you communicate with speed readers.

- Long paragraphs are usually very hard to digest. They are usually a sign that what you are writing is either very complex, or just a bit disorganised. The few readers who really want to read the detail in your case for support will find it hard.

If your paragraphs are longer than about 5 lines, try to break them up. If they are not too disorganised it will be fairly straightforward but if they are disorganised it may be easier to attend to the flow first.

Flow refers to the sequence of ideas that you present, sentence by sentence and paragraph by paragraph. Within paragraphs, good flow occurs when each sentence connects naturally to its successor. There are several ways of achieving this. If you have never thought hard about it (and I hadn’t until a few months ago), Google will find you countless sources of advice. I recommend that you read the Using English for Academic Purposes Blog, which has a section on paragraphs and flow. The basic approach is that you should always start the paragraph with the topic sentence, the one sentence that sums up the paragraph. Then, to get good flow within the paragraph you make sure that the first sentence leads naturally to the start of the second sentence, which leads naturally to the subject of the third sentence and so on. This makes it easy for the reader to read through the paragraph without having to pause and analyse the wording to work out what you mean, or having to keep several ideas in mind in order to follow what you are saying.

Flow between paragraphs is also important and again Google throws up hundreds of ways to help you make it smoother. I think that the best approach here is to reverse outline, as suggested on the Explorations of Style blog, which is full of good advice on how to make your writing more readable.

Failing to match the background to the project is a sin against Derrington’s first commandment. You won’t go to hell for the sin but you may enter the purgatory of grant rejection. The commandment requires that before you describe your project and the outcomes it will produce, you use the background section to make the case that we need exactly those outcomes. It’s a pretty basic selling technique. It persuades the customer that they want what you are selling before you describe what you are selling. I have explained before how you use key sentences to create a structure that implements the technique by creating a background section that deals with the outcomes in the same order as the description of the project, and that explains, outcome by outcome, why we need them.

The key sentences also give you the best way to fix a mismatch between background and project. Basically you create the key sentences and then you use them to re-organise your text. And then you use them to write an introduction.

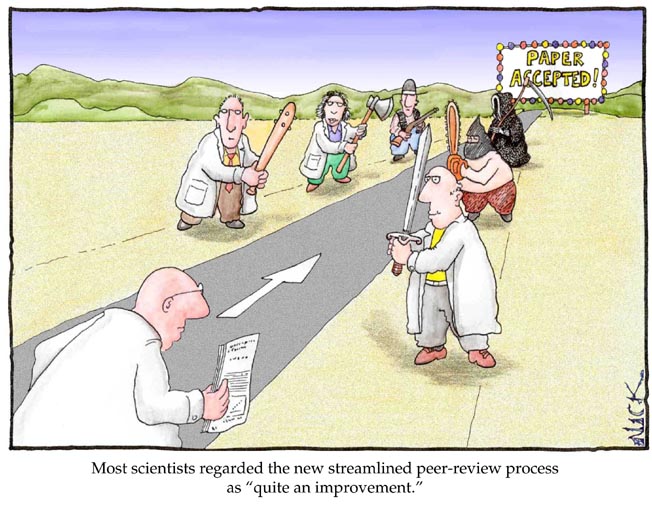

If you read a few successful grant applications you will realise that the sins are not fatal: most successful grant-writers commit them. However, the sins all make it less likely that you will get funded because they make it harder for time-pressed committee members and referees to do their job. Of course you may be lucky enough that the committee sees the merit in your application despite you making it difficult. But why take the chance?

![By Pieter Brueghel (http://gnozis.info/?q=node/2792) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Desidia_-_The_Seven_Deadly_Sins_-_Pieter_Brueghel-1024x795.png)